Publisher’s note: This is February’s “Back-In-The-Day” feature now arriving, albeit several days early!

Preface

For railroading back in the day, its time had definitely come. The industry has both matured and evolved. And what we have and witness today is the physical, observable manifestation of that evolution and maturation — certainly not apart from what any other industrial endeavor or enterprise would have encountered in its quest to get to saliency, solvency, profitability.

If you’re like me and you’ve paid attention, then you’re aware of at least some change aspect in the industry. The biggest change l’ve noticed has had to do with downsizing. Ongoing has been the abandonment of track, reductions in staff and increases in the application of automation used to get specific tasks done.

With this in mind, today’s featured “past” railroad is the Southern Pacific. In certain regards, the pike was way ahead of its time. In others, one might say, it was behind the times. The SP’s is an interesting story and one definitely worth sharing here at All About Trains.

Introduction

The Southern Pacific Railroad was many things to many people. To Theodore Judah, building SP predecessor Central Pacific, afforded him an opportunity to show to the world what this trained civil engineer was made of. To the likes of Edward Henry Harriman, by successfully folding the Espee into his vast empire of railroad properties, this meant that his railroad dominance in the West was assured. Others, meanwhile, hated the SP, it oftentimes being the object of their angst, reproach, scorn.

Southern Pacific, meanwhile, was seen by some as being all-powerful, “The Mighty SP” (for sure a less-becoming nickname it had obviously earned for its reputation whether perceived or real), laying railhead wherever and whenever it danged well pleased; that no doubt being the impression the railroad left on the minds of at least some folks.

History Lesson

There is no question that the “Mighty” SP is steeped in history. Its roots, of course, are in California, the institution itself surviving 124 years as an independent after having been founded in the state in 1872. It was in 1996 that the railroad was folded into the “Great Big Rolling” Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR).

In case you don’t know the Southern Pacific’s story, this little primer should help bring you more up to speed on this. The ‘road’s roots run deep.

The railroad itself was incorporated in California in Sacramento on Dec. 2, 1865. The intent was to construct a line from San Francisco to San Diego via Los Angeles with the ultimate goal of connecting with a line being built west from the Missouri River. The plans were reconfigured after its original charter when Congress authorized the construction of a railroad from San Francisco to the Arizona-California border near the town of Needles in the Golden State where it was to join Atlantic & Pacific rails. (The A&P was later folded into and became part of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe). Not content to rest on its laurels, Santa Fe was intent on establishing a Pacific seaport or two with which to do trading with the Orient. SP got wise to the Santa Fe’s ways and built a line of its own to Needles in an attempt to thwart additional development. But SP wanted trackage in Arizona and Mexico that Santa Fe owned and, in a surprise move in exchange for the Sonora Railway in Mexico and the Benson-Nogales, Arizona trackage, the “Friendly” relinquished its strategic Mojave-to-Needles trackage to “Uncle John’s ‘road.” By virtue of its own actions, its monopoly in the west was breached and SP suddenly found itself no longer the only game in town.

Central Pacific Plays A Pivotal Role

You can’t talk about the SP’s history and not include historical perspective on the CPRR — that’d be the Central Pacific Railroad. The CPRR’s history was previously detailed in the earlier Jun. 29, 2024 post “The Central Pacific Railroad-building Ambition Was Fanatical If Not Foolhardy.”

So, really briefly…

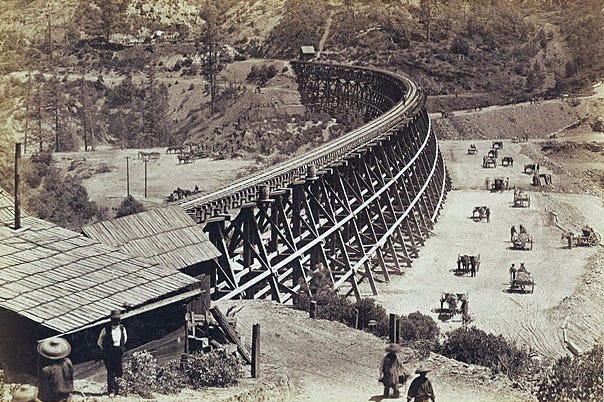

As with the Southern Pacific, the Central Pacific Railroad was incorporated as well in Sacramento, just four-and-a-half years earlier on Jun. 28, 1861, is all. Construction commenced Jan. 3, 1863 and for six long, arduous and tempestuous years, Chinese, Irish and other imported labor worked exhaustingly in many a case to help forge at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869 the joining of CPRR and UPRR railhead.

Against all manner of odds and obstacles, and despite CPRR being a blighted undertaking from day one, still, it was deemed a success.

Meanwhile, the Central Pacific, over time, not surprisingly, became a property coveted by the SP; in no way different from the then head of UPRR, top executive Harriman wanting to take sole possession of Southern Pacific to add to his then existing stable of railroad properties owned and controlled. The long and short of it is that years later, under a reorganization scheme, in fact, the CPRR had become part of the SP. This was in 1923.

Western Rail-Dominance In The 20th Century

If there was one company that epitomized corporate fiefdom, especially in California, that company would be the Southern Pacific.

With regard to its strong influence in the Golden State, and throughout the western U.S. for that matter, SP was far and away, the dominant player in California in terms of both its rail and non-rail assets. Everything from heavy rail and interurban rail, and trucking and real estate, to pipelines and telecommunications. There was seemingly nothing that SP did not have a hand in. In fact, no other transportation concern could even “touch ‘em,” as far as dominance was concerned.

How Southern Pacific got to be the frontrunner in the Golden State becomes clearer as one looks back at the company’s 20th-century history.

From the time SP was incorporated in 1865 until the moment in 1923 when it took full corporate CPRR control, the western-U.S. railroad-construction movement ran rampant. Both SP and rival UP were expanding at a rate likened to wildfire. It was also during this time that UPRR president E. H. Harriman was looking to expand his Union Pacific empire by securing control of SP. And it almost worked!

At the turn of the century, coincident with the death of SP President Collis P. Huntington (a Sacramento businessman and one of the legendary “Big Four”), UP President Harriman was issued $100 million of convertible Union Pacific bonds to use as he saw fit. He used the funds to purchase Huntington’s share of SP and CPRR stock, which amounted to 46% and 100%, respectively. However, despite Harriman’s best intentions at unifying the two corporate giants, the government did not share Harriman’s enthusiasm for keeping SP and UP unified. Subsequent to Harriman’s September 1909 death, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered UPRR in 1913 to divest itself of all SP stock, thereby dashing all hopes of a successful UP/SP combination.

Any attempt at unifying these two corporate conglomerates would now have to wait. Nevertheless, there were those occasions when, as competitors, the duo cooperated. This is evidenced by their joint involvement with regard to two business dealings in particular; the successful Pacific Fruit Express venture and the ill-fated joint takeover attempt of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad.

The Pacific Fruit Express Company, which became incorporated on Oct. 1, 1907, was a UP/SP partnership that lasted 71 years. This shared operation demonstrates just what two competing carriers can achieve when they put their collective minds to it. On the other hand, the less-than-productive acquisition of the CRI&P is a debacle that can turn the best of cooperative intentions — sour.

Here’s what transpired. In 1963, UP and SP advanced a plan to split up the Rock Island Line. During the lengthy review process, the Rock experienced a slow degradation of service, decay of its physical plant and years of red ink. By the time the Interstate Commerce Commission got around to approving the acquisition on Dec. 4, 1974, UP balked at the deal citing conditions too onerous to facilitate a beneficial merger. In addition, the condition of the Rock’s track structure was deplorable. As a result, the CRI&P was forced into outright bankruptcy, and by Mar. 17, 1975, the company formally declared insolvency, bringing all Rock operations to a halt. Despite this, Southern Pacific did benefit from the affair by claiming dominion to the Kansas City to El Paso trackage, subsequently installing it as its Golden State Route. This effectively enabled SP to compete head-to-head with not only trucking interests, but with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe for merchandise and intermodal traffic originating in the mid-west bound for west coast destinations. Without this newly acquired link for SP, its position as a comprehensive and competitive transportation endeavor was questionable.

Even with the state of flux the rail industry was in during the late 1960s and early ‘70s, the two railroads were able to persevere in spite of any misgivings that may have surfaced as a result of their business dealings, however successful — or unsuccessful — they may have been.

The tables started to turn, however, when in response to the Dec. 22, 1982, three-way Union Pacific-Missouri Pacific-Western Pacific merger, SP signed a pact with Santa Fe with the intent to merge their railroad properties. Exactly one year later, the newly formed Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corp. was created with the hope that a merger between SP and SF would be in the offing. In the eyes of SP and SF executives, expectations of a successful combination ran high, considering that, if approved, the outcome would provide a more balanced freight-rail structure in the west. Leaders of both companies were unequivocally convinced that the merger was a sure thing, that locomotives (and cabooses) of both railroads were painted in a unified scheme, sans the initials of those of its corporate partner, with that to take place come merger day. Even with the locomotive repaints and all, it was agreed that Southern Pacific and Santa Fe were to be operated separately until the final ICC ruling was rendered. But the merger was not to be.

In a 4 to 1 vote, the ICC on Jul. 24, 1986 rejected the SP+SF merger citing anti-competitive issues. On Dec. 9, 1986, the ICC was asked to reopen merger hearings and reconsider its earlier decision. Trackage rights agreements with both the Denver & Rio Grande Western and Union Pacific, and to a lesser degree with additional carriers, were reached, providing each access to several key locations on the merged system.

On Jun. 30, 1987, the ICC reaffirmed its earlier ruling and the denial was upheld. Consequently, parent SFSP was given 90 days to submit a plan to the ICC to divest itself of one or both of its railroad holdings. SFSP opted to sell the less desirable property of the two; in this case the SP. This left SP in the unenviable position of being ‘low man on the totem pole’ and in the sixth spot in terms of earnings, as far as Class I carriers were concerned.

After all was said and done, Denver & Rio Grande Western owner Philip Anschutz through Rio Grande Industries (RGI) advanced a winning bid in competition with Kansas City Southern Railway parent KCS Industries for the right to purchase the SP. All told, $1.02 billion was paid by RGI which meant that it would assume as well all of Southern Pacific Transportation Company debt that remained outstanding at the time. The two railroads received ICC merger approval on Aug. 9, 1988.

If there was one thing that characterized the SP more than any other single attribute, it was its lumber and its manifest (merchandise) traffic, and with the assumption of SP by and courtesy of RGI, its coal traffic. But, it was too little too late for the once “Mighty” Southern Pacific, for the handwriting was already on the wall regarding SP’s fate.

1996 UP/SP Merger: Comes Off But With A Hitch

What’s interesting is that the Union Pacific seemed to have its eye on SP right from the get-go. It was an on-again, off-again kind of courtship if you will; one that lasted more than a century, one ultimately ending up with the UPRR and SP tying the knot, a marriage sanctioned by Interstate Commerce Commission successor, the Surface Transportation Board, on September 11, 1996.

The consummation apparently, was in direct response to the link-up of Burlington Northern and Santa Fe that happened the year prior. I’m thinking that perhaps UPRR or SP was thinking (or maybe both were thinking) that the only way to effectively compete was by their joining forces.

On paper the idea must have been seen as sound, profound and sure. On the other hand, on the ground or in reality, it seemed anything but. As I, and I believe most observers saw it, all didn’t go exactly as planned. In other words, it came off with a hitch, as opposed to it coming off without such, as the familiar saying goes.

What happened.

A virtual meltdown is what happened. Online traffic got way bogged down. So much so, in fact, that sidings were used to store freights whose crews went dead on the (hours of service) law. It took a fairly long time for operations across the entire system to once again to become fluid like they were pre-merger. The important point is the logjam did ultimately get resolved.

I know this is going to sound so cliché, but the rest, like the above, is also history.

In conclusion…

Even though Southern Pacific is no longer with us, the legacy it left behind will no doubt not be forgotten as long as efforts like this and others to keep its heritage and name alive, are ongoing.

Notes

In an earlier version, in the caption to the sixth photo from the top the town of Aromas, the “s” at the end was inadvertently left off. The town name now appears as correct.

Updated: Jan. 25, 2025 at 7:21 p.m. PST.

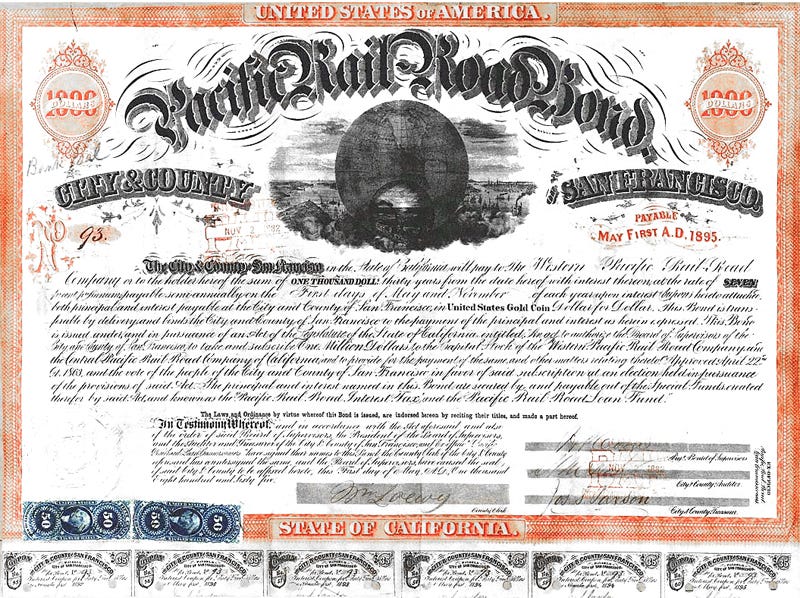

Image credits: City and County of San Francisco, California (bond); DigitalImageServices.com (scanning, reconstruction, digital restoration, and enhancement) via Wikimedia Commons (3rd); Carlton E. Watkins via Wikimedia Commons (4th); all others Alan Kandel

All material copyrighted 2025, Alan Kandel. All Rights Reserved.