Over the long haul, American railroading, since its circa 1830’s introduction, in at least one sense is little changed: The steel wheel on steel rail platform is still king.

From the railhead down, the picture pretty much looks like it did when thirteen original Baltimore & Ohio Railroad miles of track were laid from Mt. Clare Station in the heart of Baltimore to Ellicott City (then Ellicott’s Mills) to the west. Two rails placed side by side fastened to stone sleepers (ties) upon which carriages rolled, pulled by either horses or the at-the-time revolutionary contrivance known as the “Tom Thumb;” for all intents and purposes, trackside, it’s what we still see today.

Upon closer examination, advances in technology within the industry have been quite pronounced, very well documented and have not gone unnoticed. Motive-power propulsion-wise the development is self-evident, going and literally growing from “horse” power initially to steam power to today’s electric and diesel-electric operation. Gen-Sets and hybrids have recently made their way onto the scene and, I, for one, am well aware of hydrogen’s contribution to the mode, platform, sector.

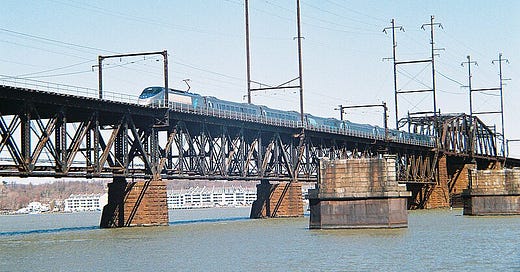

Astonishingly, perhaps even surprisingly, the 100 mph threshold was relatively quickly reached and with steam power in charge no less. However, it wasn’t until electric propulsion came along — this in conjunction with marked track-structure improvements — that a milestone on the speed front was realized. Passenger-train velocities of 125 mph on Northeast-Corridor (NEC) track aren’t uncommon with speeds reaching 150 mph courtesy of the Amtrak Acela trainsets on short NEC stretches north of New York.

While it can be argued 150 mph is exactly 50 percent faster than those record-setting 100 mph velocities reached on certain steam-powered passenger runs circa the late 19th century/early 20th century, comparatively speaking, that’s somewhat “sluggish” compared to what’s typical on Asia’s and Europe’s very high-speed train systems. I find that to be something of a disadvantage, especially considering that not so very long ago a specially prepared Train A Grande Vitesse (TGV) train in France made a record-setting 357.2 mph run, thereby breaking all previous TGV speed records. Imagine land travel where a distance of one mile is covered in 10 seconds! It’s almost incomprehensible!

Knowing this and understanding the implications, why in America, are we behind the curve, in a manner of speaking, high-speed-train-development-progress-wise? In that other countries have left us not far out of the HSR starting gate, so to speak, that, too, to me, is almost incomprehensible!

Keeping it real, what will “true” high-speed rail mean for us landlubbers here at home? For starters, it will mean freed-up air and highway space which has implications in terms of it resulting in these respective environments being far less dangerous places to fly and drive, not to mention reduced dependence on oil, fewer greenhouse gases emitted from both mobile and stationary sources, and the possibility of there being created tens if not hundreds of thousands of new jobs on the home front.

So what, if anything, can be done to speed things along?

The first thing that comes to mind is what the attitude generally of the American public is toward high speed. In this country passenger railroading is by and large almost an afterthought; at least that’s the way it seems to me. That must change if such is to make inroads in the overall transport-mode makeup that currently exists here. Roadways and airways get the lion’s share of funding — local, state, federal — with railways in a sense being relegated to the proverbial back seat in that regard. A 33 percent, 33 percent, 33 percent allocated subsidies split would be nice; not just nice, but in my opinion, de rigueur.

Secondly, rather than each mode operating in a vacuum, operations should be coordinated so that each mode supports the other two. This could and should make for a very efficient operating paradigm and help overall mobility to become more streamlined and less constrained. This isn’t rocket science.

Lastly, high-speed train travel must have affordable if not competitive pricing. It must be reasonable if we expect people to come out in droves and ride HSR trains. To make it fare-attractive, in other words. And, high-speed trains must go where patrons want and/or need to go.

There is presently an empty space where surface-based viable-travel alternatives are concerned, in my opinion. Thankfully that situation is being addressed and my sense is Americans are slowly warming up to the notion that high-speed trains are the answer to filling that empty space that I alluded to above. The African, Asian and European nations that have both established and bonafide bullet-train networks can’t all be wrong. They obviously know something that the bulk of the American citizens will soon find out for themselves first hand. We’ve come this far. Now let’s cross the finish line!

Updated: Mar. 23, 2025 at 5:20 a.m. PDT.

Image credit: © by James G. Howes, 2008. via Wikimedia Commons

All material copyrighted 2025, Alan Kandel. All Rights Reserved.

Alan, HSR can be incredibly effective, but you underestimate the ability of politicians to get in the middle of projects and royally screw things up. See how they ruined the opportunity to bring HSR to California: https://allabouttrains.substack.com/p/dump-cahsr-urges-transdef